STS-63

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (May 2008) |

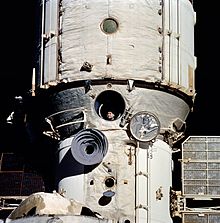

View from Discovery of Mir with the Progress M-25 (top) and Soyuz-TM Vityaz (bottom) spacecraft | |

| Names | Space Transportation System-63 |

|---|---|

| Mission type | Research Mir rendezvous |

| Operator | NASA |

| COSPAR ID | 1995-004A |

| SATCAT no. | 23469 |

| Mission duration | 8 days, 6 hours, 28 minutes, 15 seconds |

| Distance travelled | 4,816,454 km (2,992,806 mi) |

| Orbits completed | 129 |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft | Space Shuttle Discovery |

| Payload mass | 8,641 kg (19,050 lb) |

| Crew | |

| Crew size | 6 |

| Members | |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | February 3, 1995, 05:22:04 UTC (12:22:04 am EST) |

| Launch site | Kennedy, LC-39B |

| End of mission | |

| Landing date | February 11, 1995, 11:50:19 UTC (6:50:19 am EST) |

| Landing site | Kennedy, SLF Runway 15 |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric |

| Regime | Low Earth orbit |

| Perigee altitude | 275 km (171 mi) |

| Apogee altitude | 342 km (213 mi) |

| Inclination | 51.6° |

| Period | 92.3 minutes |

Mission insignia  Standing: Harris and Foale Seated, from left: Voss, Collins, Wetherbee and Titov | |

STS-63 was the second mission of the U.S.-Russian Shuttle–Mir program and the 20th flight of Space Shuttle Discovery. Dubbed the "Near-Mir" mission, it achieved the first rendezvous between an American Space Shuttle and Russia's space station, Mir. Discovery lifted off from Kennedy Space Center's Launch Complex 39B on February 3, 1995, in a night launch. This mission featured several milestones, Eileen Collins became the first female pilot of a Space Shuttle and the first extravehicular activities for both a U.K. born astronaut, Michael Foale, and an astronaut of African heritage, Bernard A. Harris, Jr. STS-63 also successfully deployed and retrieved the Spartan-204 (Shuttle Pointed Autonomous Research Tool for Astronomy 204) and executed a flyaround of Mir, a critical rehearsal for the upcoming STS-71 mission, which would mark the first shuttle docking with the Russian space station.

Crew

[edit]| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Third spaceflight | |

| Pilot | First spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 1 Payload Commander |

Second and last spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 2 Flight Engineer |

Third spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 3 | Second spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 4 | Third[a] spaceflight | |

Spacewalks

[edit]- Foale and Harris – EVA 1

- EVA 1 Start: February 9, 1995 – 11:56 UTC

- EVA 1 End: February 9, 1995 – 16:35 UTC

- Duration: 4 hours, 39 minutes

Crew seat assignments

[edit]| Seat[1] | Launch | Landing |  Seats 1–4 are on the flight deck. Seats 5–7 are on the mid-deck. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wetherbee | ||

| 2 | Collins | ||

| 3 | Harris | Voss | |

| 4 | Foale | ||

| 5 | Voss | Harris | |

| 6 | Titov | ||

| 7 | Unused | ||

Mission highlights

[edit]

| Attempt | Planned | Result | Turnaround | Reason | Decision point | Weather go (%) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 Feb 1995, 12:47:44 am | Scrubbed | — | Technical | Failure of Inertial Measurement Unit #2.[2] | ||

| 2 | 3 Feb 1995, 12:22:04 am | Success | 0 days 23 hours 34 minutes |

STS-63's primary objective was to perform a rendezvous and fly around the Russian space station Mir. The objectives of the Mir rendezvous were to verify flight techniques, communications and navigation aid sensor interfaces, and engineering analyses associated with Shuttle/Mir proximity operations in preparation for the STS-71 docking mission.

Other objectives of the flight were to perform the operations necessary to fulfill the requirements of experiments located in SPACEHAB-3 and to fly captively, then deploy and retrieve the Spartan-204 (Shuttle Pointed Autonomous Research Tool for Astronomy), a free-flying retrievable platform. Spartan-204 was designed to obtain data in the far ultraviolet region of the spectrum from diffuse sources of light. Two crewmembers were scheduled to perform a five-hour spacewalk.

Payloads flying aboard STS-63 included the Cryo Systems Experiment (CSE), the Shuttle Glow (GLO-2) experiment, Orbital Debris Radar Calibration Spheres (ODERACS-2), the Solid Surface Combustion Experiment (SSCE), the Air Force Maui Optical Site Calibration Test (AMOS) and the Midcourse Space Experiment (MSX).

Beginning on flight day one, a series of thruster burns were performed daily to bring Discovery in line with Mir. The original plan called for the orbiter to approach to no closer than 10 meters (33 ft) from Mir, and then complete a flyaround of the Russian space station. However, three of the orbiter's 44 Reaction Control System (RCS) thrusters—small firing jets used for on-orbit maneuvering—sprang leaks prior to rendezvous. Shortly after main engine cutoff, two leaks occurred in the aft primary thrusters, one of which—called R1U—was key to rendezvous. A third leak occurred later in flight in the forward primary thruster, but the crew was able to fix the problem.

After extensive negotiations and technical information exchanges between the U.S. and Russian space teams, the Russians concluded close approach could be safely achieved and the STS-63 crew was given 'go' to proceed. R1U's thruster manifold was closed and the backup thruster was selected for the approach. Ship-to-ship radio contact with Mir was achieved well ahead of time, and Titov, who had previously lived on Mir for more than a year, communicated excitedly with the three cosmonauts aboard the space station: Mir 17 Commander Alexander Viktorenko; Flight Engineer Yelena Kondakova; and Valery Polyakov, a physician who had broken Titov's record for extended time in space. After stationkeeping at a distance of 122 meters (400 ft) from Mir and with Wetherbee manually controlling the orbiter, Discovery was flown to 11 meters (36 ft) from the Russian space station on February 6, 1995 at 19:23:20 UTC. "As we are bringing our spaceships closer together, we are bringing our nations closer together," Wetherbee said after Discovery was at point of closest approach. "The next time we approach, we will shake your hand and together we will lead our world into the next millennium."

"We are one. We are human," Viktorenko responded. Wetherbee then backed the orbiter away to 122 meters (400 ft) and performed a one and a quarter-loop flyaround of Mir while the station was filmed and photographed. The Mir crew reported no vibrations or solar array movement as result of the approach.

The crew also worked extensively with payloads aboard Discovery. Flying in the forward payload bay and activated on flight day one was SPACEHAB-3. The commercially developed module was making its third flight on the Shuttle and carried 20 experiments: 11 biotechnology experiments, three advanced materials development experiments, four technology demonstrations and two pieces of supporting hardware measuring on-orbit accelerations. Improvements had been made to the SPACEHAB system to reduce demand on crew time. A new video switch had been added to lessen the need for astronaut involvement in video operations, and an experiment interface had been added to the telemetry system to allow the experiment investigator to link directly via computer with the onboard experiment to receive data and monitor status. Charlotte, an experimental robotic device being flown for the first time, also reduced crew workload by taking over simple tasks such as changing experiment samples.

Among the plant growth experiments was Astroculture, flying for the fourth time on the Shuttle. The objective of Astroculture was to validate performance of plant growth technologies in the microgravity environment of space for application to a life support system in space. The investigation had applications on Earth, since it covered such topics as energy-efficient lighting and removal of pollutants from indoor air. One of the pharmaceutical experiments, Immune, also had Earth applications. Exploiting a known tendency of spaceflight to weaken the immune system, the Immune experiment tested the ability of a particular substance to prevent or reduce this weakening. Clinical applications could include treatment of individuals suffering from such immunosuppressant diseases as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.

On flight day two, the crew deployed the Orbital Debris Radar Calibration System-II (ODERACS-II) to help characterize the orbital debris environment for objects smaller than 10 centimeters (about four inches) in diameter. A complement of six target objects of known dimensions and with limited orbital lifespans was released into orbit and tracked by ground-based radars, allowing precise calibration of radars so they can more accurately track smaller pieces of space debris in low Earth orbit.

Also on flight day two, the crew lifted with the orbiter remote manipulator system arm SPARTAN-204 from its support structure in payload bay. SPARTAN remained suspended on the arm for observation of orbiter glow phenomenon and thruster jet firings. SPARTAN-204 was later released from the arm to complete about 40 hours of free-flight, during which time its Far Ultraviolet Imaging Spectrograph instrument studied celestial targets in the interstellar medium, the gas and dust which fills the space between the stars and which is the material from which new stars and planets are formed.

SPARTAN-204 was also used for extravehicular activity (EVA) near end of the flight. Foale and Harris began their EVA suspended at the end of the robot arm, away from the payload bay, to test modifications to their spacesuits to keep spacewalkers warmer in the extreme cold of space. The two astronauts were then scheduled to practice handling the approximately 1,100 kilograms (2,400 lb) SPARTAN to rehearse space station assembly techniques, but both astronauts reported they were becoming very cold—this portion of the spacewalk being performed during a night pass—and mass handling was curtailed. This 29th Shuttle spacewalk, the first for both a UK-born astronaut and an African-American astronaut, lasted 4 hours, 38 minutes.

Other payloads: Along with ODERACS-II, the Cryo System Experiment (CSE) and Shuttle Glow (GLO-2) payloads were mounted on the Hitchhiker support assembly in cargo bay; an IMAX camera was also located here. In middeck, the Solid Surface Combustion Experiment (SSCE) flew for the eighth time. The Air Force Maui Optical Site (AMOS) test required no onboard hardware.

Coca-Cola in Space

[edit]

BioServe Space Technologies at the University of Colorado, Boulder, developed the Fluids Generic Bioprocessing Apparatus-1 (FGBA-1) in cooperation with Coca-Cola and several other groups. It dispensed pre-mixed soda for astronauts' consumption and studied their changed taste perceptions. Astronauts rated control samples before and after flight.[3] FGBA-2 flew on STS-77.

Mission insignia

[edit]The six rays of the Sun and the three stars on the right of the insignia symbolize the flight's numerical designation in the Space Transportation System's mission sequence.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Not including unnumbered Soyuz mission which failed to reach space.

References

[edit]- ^ "STS-63". Spacefacts. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ Fricke, Robert W. (June 1, 1995). STS-63 Space Shuttle report (PDF) (Report). NASA. Retrieved February 13, 2025.

- ^ "STS-63 Press Kit" (PDF) (Press release). Titusville, FL: NASA. February 1995.

External links

[edit]- NASA mission summary Archived March 20, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- STS-63 Video Highlights Archived January 2, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.